3rd May 2019

Outside Fortress Europe Excerpts

This first endnote Global Business Strategy Blog essay is based upon unabridged excerpts from Chapter Eight, Implementing Global Business Strategy, in Outside Fortress Europe: Strategies for the Global Market.

Outside Fortress Europe Excerpt

In this first of two ‘endnote essays,’ we return to the themes featured in the opening ‘foundation essays’, namely, business environment complexity, global strategic competitiveness and organizational development.

Introduction: Organizational capabilities for global business strategy success

The following list presents the research-defined business capabilities which characterise the organizational complexity we have alluded to throughout the book thus far. It also places meaningful and understandable labels to the multi-variable nature of organizational capability and competencies for the design and delivery of global business strategies.

Organizational Capabilities and Competencies for Global Business Strategy Design and Implementation.

-

-

- Passionate, strong leadership.

- Long-term perspective.

- Market leadership.

- (Potential) market share transfer from one market to another.

- (Potential) customer share transfer, from one segment to another.

- (Potential) customer loyalty leverage, e.g. cross-selling, upselling, brand stretching, brand extensions (see Chapter Six, Strategic Marketing and Global Brand Management, for insights and discussion).

- (Potential) image transfer across global market segments, e.g. MTV, Spotify, Netflix, Apple, Lea & Perrins Worcester sauce.

- Market knowledge competencies (see Chapter Five, Analysing Global Markets and the Intelligent Company, for insights and discussion).

- Innovation competencies, e.g. 3M, Google, PepsiCo, Danone, GE.

- Organizational flexibility: mechanistic versus organic (see Chapter Eleven, A Strategic Perspective on Managing Change, for insights and discussion).

- Technology superiority, e.g. Tesla, IBM, Intel, Cisco Systems, German Mittelstand (SME) companies.

- Internet competencies, e.g. Amazon, Alibaba, Walmart (e-procurement, supplier extranets etc.).

- Supply chain competencies, e.g. Dell, Toyota, Nissan, Primark, Apple.

- Ability to follow key customers in global markets, e.g. IBM (‘Solutions for a Small Planet’), WPP (advertising and marketing services – ‘think global, act local’).

- Post-acquisition integration competencies, e.g. Unilever, GSK, P&G/Gillette, Reckitt Benckiser.

- Network opportunities: joint ventures, strategic alliances, channel partnerships, etc. (see Chapters Nine and Twelve for insights and discussion).

- Financial strength and stability, e.g. Apple, Microsoft, BMW, Siemens, Carrefour.

- (Relative) cost-to-serve advantage, e.g. Gillette, Wrigley’s, SAP, Facebook, Bosch, Matsushita.

- Price flexibility (low-competitive-high), especially when aligned with global brand management capabilities, e.g. the Swatch Group and its multiple ‘brand families’ (Blancpain, Longines, Omega, Rado, Tissot).

- Countertrade competencies, especially for latent demand where the need is clear, but the funds are lacking, e.g. GE power stations in India exchanged for a percentage of energy output earnings.

- Relevant product quality for selected country markets, e.g. don’t ‘over-engineer’ products for relatively poor markets and segments; or plan an upgrade path, e.g. Philips Medical Systems which build an installed base of ‘base-line’ scanners in emerging markets with an eye on future add-on modules being purchased.

- Services, combining ‘feel-good-factor’ with revenue generation potential.

- Customisation ability, especially ‘mass customisation’ for consumer markets (e.g. Swatch) or B2B markets, e.g. IBM Key Account Management programmes.

- Channel management competencies, e.g. Gillette, parent company P&G, Unilever; SAP and IBM in SME market spaces.

- Relevant product range for the country market, e.g. McDonald’s, EuroDisney (eventually), Philips Medical Systems.

- Global brand management, e.g. Reckitt Benckiser (brands include: Dettol, Durex, Mucinex, Nurofen, Scholl, Strepsils, Veet, Clearasil, Gaviscon, Lysol, Harpic, Air wick).

- Employee engagement and investment.

- Anything else relevant to the specific global business strategy opportunity?

-

Note that the last bullet point of the above list relates to our consistent use of the Anything else? variable even where the most comprehensive of lists is presented. This enables the construction of a common approach to strategic planning while simultaneously accommodating the diversity of organizational form and global-local market conditions.

Hard and soft factors explaining organizational implementation success

When exploring marketing strategy and global strategic management from the extremes of industrial economics and organizational behaviour, it is possible to identify two broad categories relating to explanations of organizational implementation performance: hard and soft factors. In the popular textbook Strategy Synthesis, for example, de Witt and Meyer (2014) argue that competitive advantage arises from resolving strategy tensions (paradoxes) and they provide the following examples:

Strategy Process:

-

-

- Strategic Thinking: Logic versus Creativity.

- Strategy Formation: Deliberateness versus Emergence (see Chapter Two, Strategic Planning and Organizational Design for Global Business Strategy).

- Strategic Change: Revolution versus Evolution.

-

Strategy Content:

-

-

- Business Level Strategy: Markets versus Resources.

- Corporate Level Strategy: Responsiveness versus Synergy.

- Network Level Strategy: Competition versus Cooperation (see Chapter Nine, Acquisitions, Joint Ventures and Strategic Alliances for Global Business Strategy, for insights and discussion).

-

Strategy Context:

-

-

- Industry Context: Compliance versus Choice.

- Organizational Context: Control versus Chaos.

- International Context: Globalization versus Localization (see Chapter Six, Strategic Marketing and Global Brand Management, for insights and discussion).

-

Purpose:

-

-

- Organizational Purpose: Profitability versus Responsibility (see the sections below relating to organizational and investor responsibility in global business strategy).

-

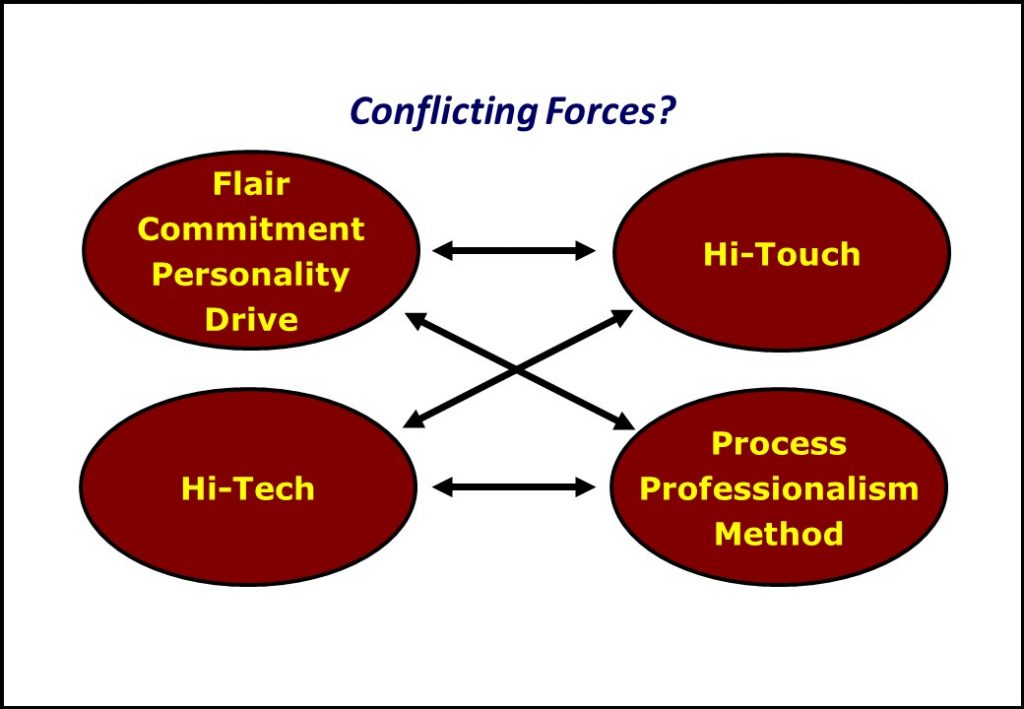

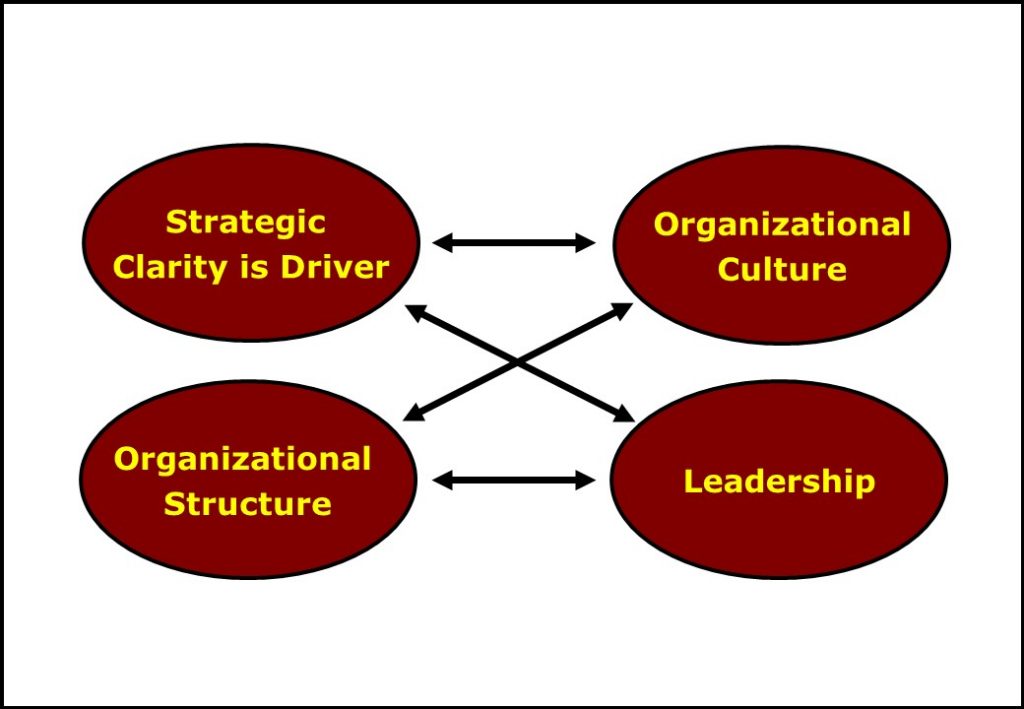

We examine many of these issues in more detail from a more analytical perspective in Part Three of the book, Creating Organizational Advantage, and some should be recognisable from earlier discussions as indicated by the cross-references. For our purposes here, meanwhile, Figure 1 summarises in four key categories (ovals) the multiple dimensions of strategic management and organizational design which we have addressed thus far in this book.

Figure 1 also poses a question: on the surface at least, and despite the interdependencies indicated by the four double-headed arrows, there appear to be inherent contradictions in the factors mentioned in the ovals. But it is our contention that the answer to the question Conflicting Forces? is, to cite the legendary lyricist Ira Gershwin, it ain’t necessarily so. It ultimately depends on how conflict potential is managed.

The best metaphor the author came across to clarify this point came from a Harvard Business School Professor at a teaching conference he attended in Arizona. The Prof. held a pen aloft and observed that the object had a potential acceleration of 9.81m/s2 – but only if he dropped it. Much of effective leadership and management relates to acknowledging the potential for conflict to arise within organizations, identifying its sources and addressing it in a timely and appropriate manner, i.e. don’t drop the pen! (see the section ‘Explaining Inter-functional Conflict’ in Chapter Four, Theories of Strategy and Competition, for a discussion on organizational solutions to the marketing/production and finance/logistics functional conflict trade-offs).

Reverting to Figure 1, in the previous chapter the predominant emphasis was on Process/Professionalism/Method both in the ‘Framework for Global Business Strategy Success’ and in the ‘Operational Go-to-Market Plan’. But we also emphasised the importance of ‘Management Judgement’ in global business strategy decision-making (see the narrative relating to Figure 53, ‘The Country Market Selection Process’), captured in the upper-left side oval here as Flair/Commitment/Personality/Drive.

Similarly, with reference to the Hi-Tech oval, if the futurologists and the pundits are to be believed, robots and Artificial Intelligence will rule the organizational roost sometime soon (see The Economist, 2018, special report, ‘AI in Business: GrAIt expectations’, March 31st). Yet while it is clear that many organizational tasks are ripe for automation there are many others that will never replace the Hi-Touch sensitivity of human engagement. And new industries will emerge and create new employment opportunities, just as they always have done since the Luddites took their hammers to the (weaving) machines in the days of Adam Smith and David Ricardo. And, as Peter Drucker (1974) presciently observed: “We are becoming aware that the major questions regarding technology are not technical but human questions”.

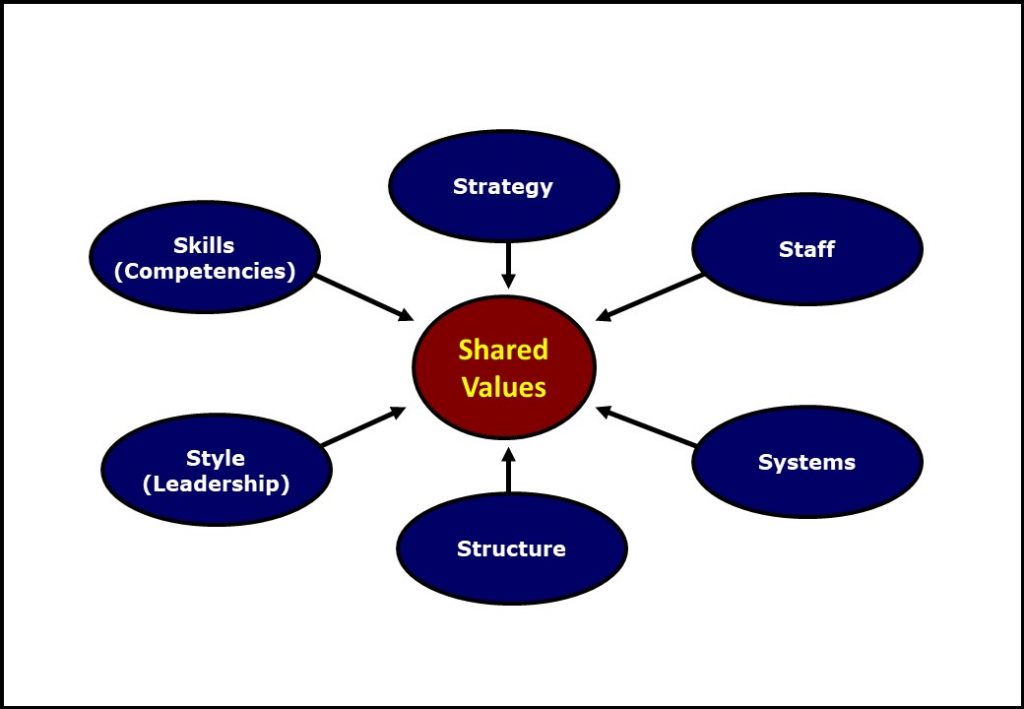

We have mentioned In Search of Excellence by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman (1982) on numerous occasions throughout the book, mostly tilting towards a critique of its oversimplification of complex organizational phenomena. But, as we discussed in the Prologue, there are some management ideas that genuinely influence the way in which managers think and organizations operate and there is no doubt that In Search of Excellence sits comfortably in this category: not all managerial science and thinking has its roots in dull empiricism. Figure 2 presents the adapted McKinsey 7S Excellence factors.

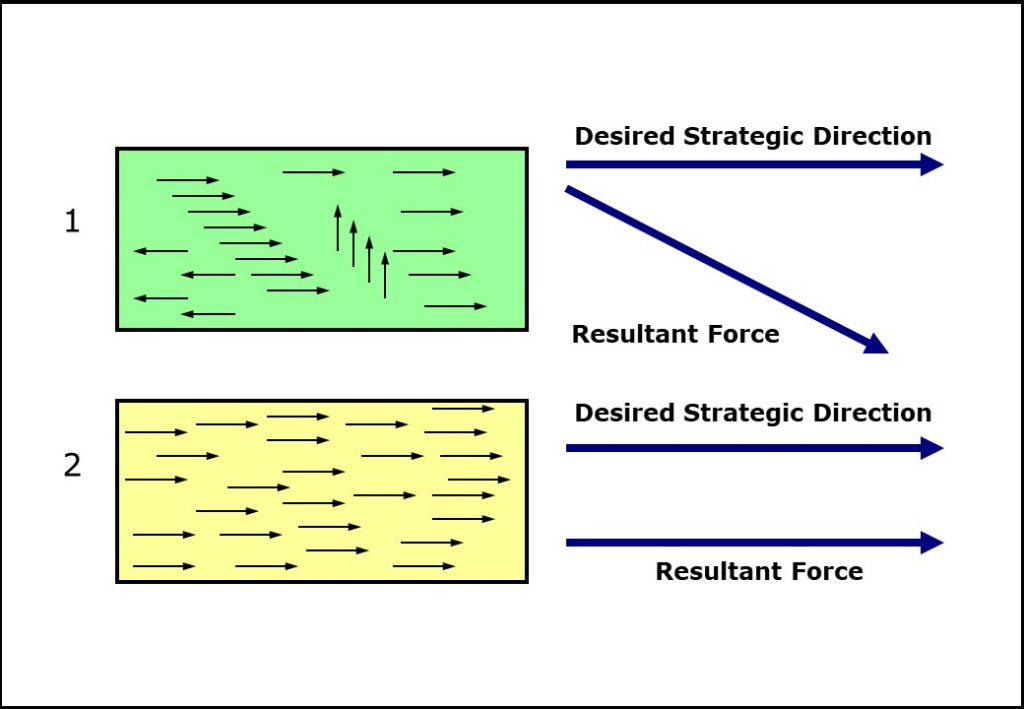

The adaptation referred to is that Shared Values replaces the original ‘Super-ordinate Goals’ and the arrows in the graphic depicts a systemic perspective, i.e. everything else feeds into this particular S. The book was widely interpreted as being a metaphor for organizational culture and was criticised in some quarters for its ‘soft Ss’: how can they be measured and, therefore, generalised as Lessons (as claimed in the subtitle of the book)? It is this author’s opinion and experience that in many areas of management it is intangible (soft) factors that have stronger explanatory power than many quantitative metrics, for example, Experiential Customer Value and Brands as discussed in Chapter Six, Strategic Marketing and Global Brand Management. With this observation made, Figure 3 aims to demonstrate how the ‘soft S’ Shared Values can be used to explain organizational culture and change with reference to vectors, a ‘hard’ mathematical construct used widely in physics (OED definition of vector: A quantity having direction as well as magnitude).

Boxes 1 and 2 in Figure 3 represent two hypothetical organizations in a similar hypothetical business case scenario; the arrows inside the boxes are vectors and each one represents a number of functionally unrelated employees. Both organizations have held a ‘strategic review’ and the executive teams of each have articulated a Desired Strategic Direction. Organization 1 is in trouble: for whatever reasons, 60% of employees support the change (amongst them the ‘evangelists’ – see Chapter Eleven, A Strategic Perspective on Managing Change); 20% oppose the change (amongst them the ‘Luddites’); 20% – represented by the vertical vectors – don’t care (amongst them the ‘volunteers’, happy to take the redundancy cheque if offered and typically amongst the most gifted and mobile employees). Add up the vectors, compute the Resultant Force and observe what strategy professors might be tempted to describe as ‘strategic drift’ (see, for example, Johnson et al., 2017). Organization 2 is on track for success, the shared values indicating likely success, but only if the strategic direction makes sense, strategy-wise. In sum, here we present ‘hard’ support for the softest of Ss.

(We apologise to mathematicians for usurping their vectors and no doubt misrepresenting their predictive power. The 60-20-20 percentage change challenge has been observed on numerous occasions with reference to organizational transformation ‘programmed change’ initiatives; in the public sector especially, it is not uncommon that the ‘redundancy volunteers’ will be re-hired and be back at work on the next day at the same desk: employed again, but now as consultants).

Building a market-driven, customer-centric organization

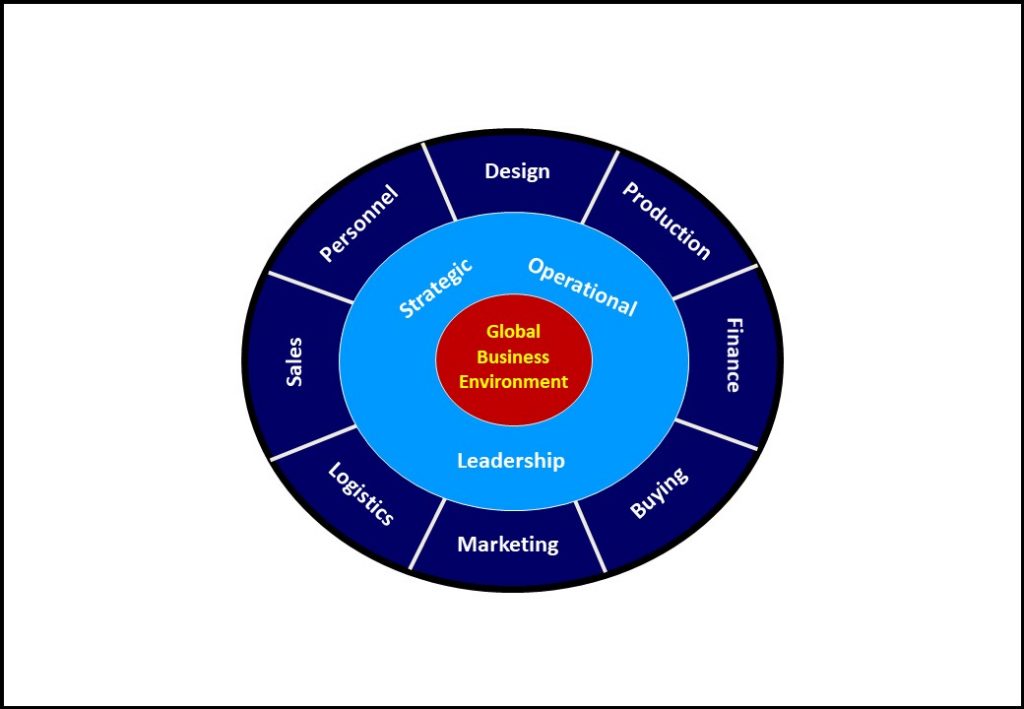

Earlier in the chapter, we argued for an ‘outside-in’ approach to business environment sensing and scanning, especially in turbulent global business environments. Figure 4 reflects this perspective and, building upon our previous discussion of organizational culture, is followed by a brief narrative on how to build a customer-centric organization based on the fundamental premise that everyone’s pay-check, regardless of function or hierarchical position, is derived from the markets their company compete in.

Since marketing and sales physically work at the company-customer interface the responsibility for instilling a marketing culture should rest with a ‘marketing department’ although, as we concluded at the end of Chapter Six, Strategic Marketing and Global Brand Management, the marketing function is typically ill-defined and fragmented in many large companies. Also, given that defining a company’s culture is a leadership responsibility we suggest that this direction should come from the CEO (e.g. Lord Browne of BP, as previously discussed) and preferably a Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) with Board status (e.g. Abbey Kohnstamm of IBM, as previously discussed). The key principles and practicalities of building a customer-centric organization which are listed below align closely with our earlier discussion of internal marketing in this chapter.

Instilling a Marketing Culture.

-

-

- Signal top management support:

- Lead by example;

- Create a suitable climate.

- Establish a task force:

- CEO, CMO, board, key managers;

- Decide the internal marketing strategy.

- Recruit expert consultants:

- Know-how, culture-free;

- Central task-force advisor.

- Recruit top marketer per Strategic Business Unit (SBU):

- Politically shrewd;

- Experienced, tough and able.

- Fund marketing training:

- Functional heads, then all others;

- Know marketing’s strategic importance.

- Recruit marketing specialists:

- From rivals and best-in-class marketing companies;

- From reputable business schools.

- Encourage a market-led, customer-focused company culture:

- Signal expectations and rewards;

- Promote early adopters;

- Encourage all others.

- Install an internal marketing system, to include:

- Intelligence gathering;

- Internal TOWS appraisal;

- Strategy planning;

- Action routines;

- Control mechanisms.

- Signal top management support:

-

Working with Other Functions.

-

-

-

- Build marketing’s professional image.

- Communicate and interact often.

- Recognise their equal importance for business performance and success.

- See their perspective, strengths and problems.

- Build allies and relationships.

- Be tactful and harmonious.

- Share ‘ownership’ of good ideas.

- Don’t waste finance and resources on ‘pet projects’, e.g. certain sponsorship deals which don’t support the brand but do satisfy the marketing manager’s personal proclivities.

- Avoid unnecessary customisation, price cuts, credit and schedules.

- Always stress the common-sense view, e.g., we are all consumers, what do we expect from our own purchasing experience? Why would we behave towards our customers in a manner which would dissatisfy us as consumers?

-

-

Internal Marketing Goals:

The following list provides examples of the rationale underpinning the importance of internal marketing for global business strategy success:

-

-

- To secure implementation of external marketing plans.

- To remove internal resistance to marketing.

- To secure the support of deciders (managing-up).

- To secure the enthusiasm of implementors.

- To create a responsive organization.

- To shape the attitudes and behaviours of contact personnel.

-

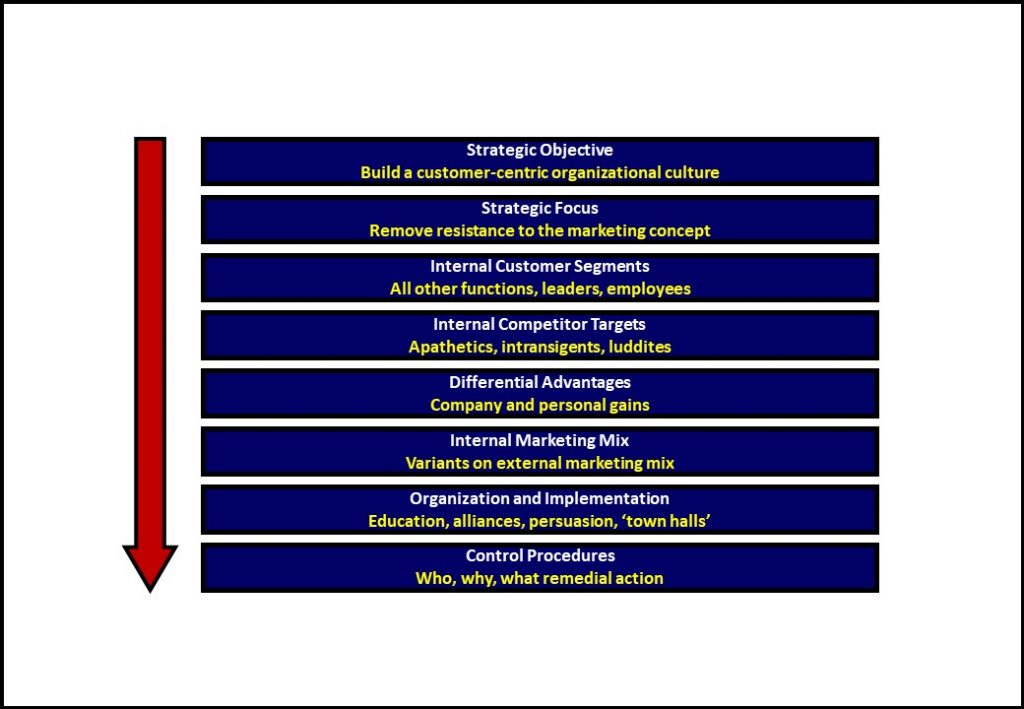

Figure 5 adopts the ‘Go-to-Market Plan’ elements from the previous Chapter and applies them to the ‘internal marketing concept’.

There is limited evidence that such a formalised process is currently being used by companies other than that the idea may be being discussed in marketing training programmes; indeed, the previously-cited research of Christopher et al. (2002) suggests that, where internal marketing is observed, it is likely to be informal in character. This doesn’t negate the ideas being presented here; rather, it suggests a research agenda for academics and a mindset change for organizations. Figure 6 presents the internal marketing mix.

In contrast to the lack of evidence in support of the benefits of internal marketing planning, there is an abundance of research relating to the ‘product’ and ‘price’ components of the internal marketing mix shown in Figure 6, the majority of which relate to change management (see Chapter Eleven, A Strategic Perspective on Managing Change, for further detail, discussion and debate).

If pushed to justify the idea of the internal marketing concept or the importance of the operational internal marketing plan we make three observations:

-

- It is not just ‘another’ management gimmick, a common assertion/accusation it endures, especially from non-marketing functional personnel.

- There are many misperceptions about what marketing is (see Chapter Six, Strategic Marketing and Global Brand Management) and it needs to be emphasised that internal marketing is not about ‘selling’ a way of working; rather, its purpose relates to creating a common-sense customer-centric organizational culture.

- We pay homage to the doyen of management thought, Peter Drucker, for the clarity of his explanation of the substantive importance of the ‘everybody does marketing!’ philosophy:

Marketing is too important to leave to a marketing department. Marketing is so basic that it cannot be considered a separate function. It is the whole business seen from the point of view of its final result, that is, from the customer’s point of view.

Strategy and organization in global business strategy

Figure 7 sets the scene for the subject matter of Part Three of the book, Creating Organizational Advantage.

Exploring Figure 7, Organizational Structure and Organizational Culture in combination relate to organizational design, a topic touched upon in Chapter Two, Strategic Planning and Organizational Design for Global Business Strategy: A Historical Perspective, and which will be developed in more depth in Chapter Ten, Theories of Organizational Behaviour and Strategic Management, and Chapter Eleven, A Strategic Perspective on Managing Change. We briefly discuss the role of Leadership in global business strategy in the next section. Strategic Clarity, meanwhile, has dominated Part Two of the book, Global Business Strategy, especially Chapters Five and Six where we introduced the concept of the Intelligent Company and the importance of market segmentation alongside the role of global brand positioning for building sustainable differential advantage through multiple value propositions (as discussed in Chapter Six, Strategic Marketing and Global Brand Management).

Concluding remarks

In this chapter we have aimed to reinforce a claim that we have repeated throughout the book: if a strategy cannot be implemented, it’s not a strategy at all. We have combined a discussion of key scholarly debates with a description of a proven method of working. We have returned again to our common theme of praxis: A way of thinking, a way of working. And we conclude with an observation on inspirational leadership from Mahatma Gandhi:

Your beliefs become your thoughts, your thoughts become your words, your words become your actions, your actions become your habits, your habits become your values, your values become your destiny.

In Part Three of the book, Creating Organizational Advantage, we explore the complexity of achieving an effective, efficient and ‘agile’ approach to global business strategy in the context of unprecedented business environment change on multiple interconnected criteria.

Recommended resources for further inquiry

For readers interested in a more detailed exploration of the subject of creating a market-oriented, customer-focused competitive organization, the author’s recommended book, based upon the multiple criteria presented in the ‘Introduction to the Global Business Strategy Blog’ and extracted here is: Piercy (2016), Market-Led Strategic Change: Transforming the Process of Going to Market.

For a brief look at leadership in global business strategy see The Global Business Strategy Album post of 8th March 2019: Chelsea 0 Manchester City 0: A leadership dilemma. This blog entry is also based upon an excerpt from Chapter Eight, Implementing Global Business Strategy, in Outside Fortress Europe: Strategies for the Global Market.

Outside Fortress Europe Excerpt References

Christopher, M., Payne, A., & Ballantyne, D. (2002). Relationship Marketing: Creating Stakeholder Value (2 ed.). Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

de Wit, B., & Meyer, R. (2014). Strategy Synthesis (4 ed.). Andover: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Drucker, P. F. (1974). Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices. London: Heinemann Professional Publishing.

Economist. (2018, March 31st). Briefing: AI in Business – GrAIt expectations. The Economist, 1-12.

Frynas, J. G., & Mellahi, K. (2014). Global Strategic Management (3 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Angwin, D., & Regner, P. (2017). Exploring Strategy: Text and Cases (11 Ed.). Harlow: Pearson.

Peters, T. J., & Waterman, R. H. (1982). In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies. New York: Harper & Row.

Piercy, N. F. (2016). Market-Led Strategic Change: Transforming the Process of Going to Market (5 ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Please click/tap your browser ‘Back’ button to return to the location navigated from. Alternatively, click/tap the ‘Antique Keyboard’ graphic below to navigate to The Global Business Strategy Album page.

All content © Colin Edward Egan, 2022